It is only through solidarity, compassion and radical reimagining that we can build a more just and joyful world for all of us.

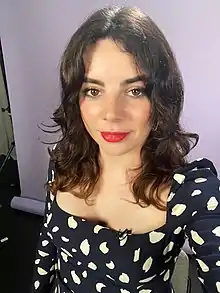

Shon Faye (born 27 March 1988) is an English writer, editor, journalist, and presenter, known for her commentary on LGBTQ+, women's, and mental health issues. She hosts the podcast Call Me Mother and is the author of the 2021 book The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice.

Quotes

The Transgender Issue (2021)

- The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice. Allen Lane. 2021. ISBN 978-0-241-42314-1.

Prologue

- The liberation of trans people would improve the lives of everyone in our society. I say 'liberation' because I believe that the humbler goals of 'trans rights' or 'trans equality' are insufficient. Trans people should not aspire to be equals in a world that remains both capitalist and patriarchal and which exploits and degrades those who live in it. Rather, we ought to seek justice – for ourselves and others alike. Trans people have endured over a century of injustice. We have been discriminated against, pathologized and victimized. Our full emancipation will only be achieved if we can imagine a society that is completely transformed from the one in which we live.

- The demand for true trans liberation echoes and overlaps with the demands of workers, socialists, feminists, anti-racists and queer people. They are radical demands, in that they go to the root of what our society is and what it could be. For this reason, the existence of trans people is a source of constant anxiety for many who are either invested in the status quo or fearful about what would replace it. In order to neutralize the potential threat to social norms posed by trans people's existence, the establishment has always sought to confine and curtail their freedom. In twenty-first-century Britain, this has been achieved in large part by belittling our political needs and turning them into a culture war 'issue'. Typically, trans people are lumped together as 'the transgender issue', dismissing and erasing the complexity of trans lives, reducing them to a set of stereotypes on which various social anxieties can be brought to bear. By and large, the transgender issue is seen as a 'toxic debate', a 'difficult topic' chewed over (usually by people who are not trans themselves) on television shows, in newspaper opinion pieces and in university philosophy departments. Actual trans people are rarely to be seen.

- ‘Trans’ [...] is an umbrella term that describes people whose gender identity (their personal sense of their own gender) varies from, does not sit comfortably with, or is different from, the biological sex recorded on their birth certificate based on the appearance of their external genitalia. The standard view of how sex and gender manifest in the world is as follows. Babies born with observable penises are recorded as male, referred to and raised as boys, and as adults are men; babies born with observable vulvas are recorded as female, referred to and raised as girls, and as adults are women. To be trans is, on some level, to feel that this standardized relationship between one’s genitalia at birth and the assignment of one of two fixed gender identities that are supposed to accurately reflect your feelings about your own body has been interrupted. How the person who experiences this interruption reacts to it can vary hugely – which is why ‘trans’ is a catch-all word for a diverse range of identities and experiences.

- When we talk about trans people, we’re usually referring to individuals who were either recorded as male at birth but who understand themselves to be women (trans women) or, vice versa, were recorded as female at birth but who understand themselves to be men (trans men). Not all trans people, however, find simply moving between the pre-existing categories of man and woman satisfactory, accurate or desirable. Such trans people, who are less well understood, generally unsettle mainstream society more than trans men and women, because they challenge not only the prevailing idea that birth genitals and gender are inseparable, but also the idea that there are just two gender categories. Often, these people are accused of making up their experience out of a need for attention or a desire to feel special – though in reality the political, economic and social costs for such ‘non-binary’ trans people (who don’t straightforwardly see themselves as men or women) can be immense.

Introduction

- Suicide attempts occur at a higher rate among trans people than the general population. Indeed, the statistics are truly alarming: research by the UK charity Stonewall published in 2017 found that 45 per cent of trans young people had attempted suicide at least once. Yet, behind the statistics are individuals, suffering in private and leading complex human lives: there is rarely one simple explanation for such a tragedy.

- In the final months of her life, when she must have been experiencing a degree of mental anguish, Lucy Meadows was bullied, harassed, ridiculed and demonized by the British media. Her death remains one of the darkest chapters in the British trans community’s history, and one of the most shameful episodes in the long and shameful history of the British tabloid press. Even if she was struggling in other ways, Meadows had not been a public figure or a celebrity, nor had she ever sought to be. She had wrestled privately with gender for many years, and her decision to transition was, by all accounts, not taken lightly. All she had done was to be trans and to be honest about who she was, continuing with a job she had been good at in a school that supported her. Her story was not remotely in the public interest. At the inquest into her death, the coroner, Michael Singleton, stated that the media should be ashamed of their treatment of Meadows. Summing up his verdict, Singleton turned to the assembled press in the court gallery and told them, ‘Shame on all of you.’

- By the end of the 2010s, trans people weren’t the occasional freak show in the pages of a red-top tabloid. Rather, we were in the headlines of almost every major newspaper every single day. We were no longer portrayed as the ridiculous but unthreatening provincial mechanic who was having a ‘sex swap’; now, we were depicted as the proponents of a powerful new ‘ideology’ that was capturing institutions and dominating public life. No longer something to be jeered at, we were instead something to be feared. Soon after the Lucy Meadows inquest, that fleeting opportunity to shed light on the bullying of trans people evaporated. In the intervening years, the press flipped the narrative: it was trans people who were the bullies.

- The media agenda with respect to ‘the transgender issue’ is often cynical and unhelpful to the cause of trans justice and liberation. Media coverage of the trans community rarely seems to be driven by a desire to inform and educate the public about the actual issues and challenges facing a group who – as all evidence indicates – are likely to experience severe discrimination throughout their lives. Today, the typical news item on trans people features a debate between a trans advocate on one side and a person with ‘concerns’ on the other – as if both parties were equally affected by the discussion. As trans people face a broken healthcare system – which in turn leaves them with a desperate lack of support both with their gender and the mental health impacts of the all-too-commonly associated problems of family rejection, bullying, homelessness and unemployment – trans people with any kind of platform or access have tried to focus media reporting on these issues, to no avail. Instead, we are invited on television to debate whether trans people should be allowed to use public toilets. Trans people have been dehumanized, reduced to a talking point or conceptual problem: an ‘issue’ to be discussed and debated endlessly. It turns out that when the media want to talk about trans issues, it means they want to talk about their issues with us, not the challenges facing us.

- Human beings rely on familiarity to understand and empathize with others, and we find it easier to extend compassion to those we can relate to. Given that, like any minority, trans people are unfamiliar to the average person, we rely more heavily on media representation, on political solidarity from people who aren’t trans and vocal, and ongoing support from public institutions to create the right conditions for understanding and compassion from the rest of society. By the same token, we’re especially vulnerable to the spread of misinformation, harmful stereotypes and repeated prejudicial tropes. And the latter, unfortunately, are widespread in public culture, just as they have been throughout history. Trans people are discriminated against, harassed and subjected to violence around the world because of deep prejudices that have been embedded into the fabric of our culture, poisoning our capacity to empathize, and even to accept trans people as fully human.

- It is only through solidarity, compassion and radical reimagining that we can build a more just and joyful world for all of us.

Chapter One

- While the media seems all too happy to focus on trans children’s right to participate in activities alongside their peers (or, indeed, on trans children’s very existence), there is little coverage of one of the most pressing problems: the fact that they are significantly more likely to experience discrimination, harassment and violence at home or at school. Sometimes, horrific stories hit local news headlines, such as the trans teenage boy whose face was slashed by a gang of teenagers in Witham, Essex, or the eleven-year-old trans girl in Manchester who, after months of bullying, was shot with a BB gun at school. To date, though, the national media has more or less completely failed to explore the ways in which such egregious incidents form part of a wider pattern of abuse of trans children.

- It is the adult world, though, that instils and nurtures prejudice.

- The shadow of Section 28 fell heavily: the effect of suppressing education about LGBTQ+ issues was not only to prevent LGBTQ+ children existing openly at school but, just as perniciously, to create a culture of silence that allowed prejudice among kids and staff alike to flourish unchallenged. Queer young people, for their part, were forced to internalize a constant drip-feed of humiliation, often (like me) not wanting to speak out for fear of making a horrible situation even worse. Having to absorb such humiliation in childhood is, unsurprisingly, something associated with a range of negative mental health outcomes later in life. Section 28 must be remembered and condemned for what it was: a staggering dereliction of duty on behalf of Britain’s policymakers towards the country’s young people.

- Everyone’s got their own battles to fight.

- Family rejection and estrangement have devastating long-term health implications. They also have a material impact. For some kids, the only option is leaving home. Others have no option at all: their parents kick them out. As a result, trans teenagers and young adults in Britain are much more likely to experience homelessness than their cisgender peers. [...] A minority within a minority, trans young people are disproportionately over-represented in the homeless population: one in four trans people have experienced homelessness.

- In the media, much of the focus on ‘trans rights’ in recent years has been on legislative rights (such as streamlining the process for legal gender recognition or having a gender-neutral passport), and on social conduct, such as checking a person’s pronouns. This emphasis stems in part from a media agenda set by cisgender people, often – as we’ve seen – for the purposes of creating controversy and fuelling a culture war. As a result, like many movements formed around an aspect of personal identity, class politics and a broader critique of capitalism have become sidelined in the trans movement. Besides the time and energy trans people have to spend defending civil rights and social courtesies, there’s a pretty straightforward reason for this. In any minority group, those who have the time, resources and political access to lead the charge for recognition and better treatment tend to be the middle-class members, who don’t appreciate the urgent issues of poverty and homelessness that for many can impede participation in activist movements. This representational imbalance leads to ‘single issue’ priorities, which emphasize the personal freedoms of the individual over the economic liberation of the entire minority group. Trans politics is no different. Poverty and homelessness are rarely framed as ‘trans issues’ in the media – or even by large LGBTQ+ lobby groups.

- Many homeless trans people stay off the streets by ‘sofa surfing’: either staying with friends or, in some cases, exchanging sex for a place to stay. Inevitably, some end up sleeping rough. For trans people on the streets, life can be brutal.

- Ending homelessness is an important political goal for society as a whole; it is especially important for trans people.

- Conversations around domestic abuse and the dwindling provision for survivors usually focus on the most common scenario: heterosexual couples with a (cisgender) male perpetrator and a (cisgender) female survivor. Yet trans people face extraordinarily high rates of domestic abuse at the hands of their partners.

- Trans people may have relationships with cisgender people or other trans people, and date men, women or non-binary people. This reality is not often represented in mainstream media, with the result that lots of trans people are led to believe that transitioning may mean the end of their love life. At one point, I was one of the many trans people who believed, incorrectly, that I would be fundamentally unlovable to anyone who knew I was assigned a different gender at birth. While I soon learned that this wasn’t the case, I also realized – as a trans woman who onlydated men – that there were men out there who could simultaneously be attracted to me and also be abusive. This was particularly apparent on dating apps, where I was always open about being trans. If men initiated messaging and I declined their advances, it was not uncommon to receive a torrent of misogynist and transphobic abuse. Online, you can simply block a stranger who exhibits such malicious behaviour. Real-life domestic abuse, however, is often insidious and incremental, with the abuser creating a sense of dependence in the abused while eroding their self-esteem. The negative messages trans people receive from society about their bodies, their desirability as partners, and their worth as individuals can make them especially susceptible to emotional, sexual and physical abuse by partners.

- The reality of trans life today is often hidden from public view.

- In all this, it cannot be emphasized enough that the political demands of trans people align with those of disabled people, migrants, people with mental illnesses, LGB people and ethnic minorities (and, needless to say, trans people can be found within all of these groups). This overlap between the needs of different marginalized people must be stressed because the illusion that trans people’s concerns are niche and highly complex is often a way to disempower them. The emphasis on the ‘minority’ status of minorities keeps them focused on explaining their difference in public discourse, so that they can be continuously batted away as an aberration or minor concern. In the specific case of trans people, this disempowerment begins at the most fundamental level: with our bodies and our right to exercise autonomy over them without interference by society. If we are to liberate all trans people socially, we must begin with the liberation of the physical trans body.

Chapter Two

- First, one of the most important – and, for many, confusing – questions: why do some trans people need medical intervention at all? Dysphoria, the antonym of ‘euphoria’, is the clinical term now used to describe the intense feeling of anxiety, distress or unhappiness some trans people feel in relation to their primary sex characteristics (genitals), their secondary sex characteristics (breasts, facial hair, menstruation, face shape, voice) or how these physical traits cause society to interact with them, by perceiving them as a male or female. Previously called ‘gender identity disorder’ and, before that, ‘transsexualism’, gender dysphoria is the name given to an experience many trans people struggle with, which can be helped by medical intervention. Although the term is widely used within the community, different trans people can experience dysphoria in very different ways, and so might have different clinical needs.

- Gender dysphoria is a rare experience in society as a whole, affecting about 0.4 per cent of the population, which can make it hard to explain to the vast majority of people, who have not experienced it. To get around this, we often rely on metaphors. The clumsy phrase ‘born in the wrong body’ has become the favoured soundbite in popular media. Clumsy because – and this must be stressed – many trans people do not think this describes dysphoria at all well. To my mind, the trans writer Andrea Long Chu expresses it more accurately: ‘Dysphoria,’ she says, ‘can feel like heartbreak.’ Heartbreak, its incapacitating grief and the sense of absence and loss which activate the same parts of the brain as physical pain, can be so all-consuming it interferes with your everyday life. So, too, dysphoria. For me, at least, this is a much richer way of describing how many trans people experience distress with their bodies – indeed, how I felt until I medically transitioned.

- Dysphoria, it should be said, is not a precondition of being trans. According to some research, as many as 10 per cent of those who positively identify as trans men, trans women, non-binary people and various other terms do so without any feelings of dysphoria. It is sometimes incorrectly assumed that trans men and women experience dysphoria and non-binary people do not, when in fact some non-binary people feel themselves to be in great need of medical assistance, and some trans men and women seek none at all. Nevertheless, most trans people experience dysphoria to some degree.

- For those who need them, medical transition and contraception or abortion are – or should be – about the bodily autonomy of the individual, their right to mental well-being and the freedom to carve out their own destiny in defiance of prevailing gender roles. (These roles, should we need reminding, frame women as vessels for reproduction and trans people as threats to the strict separation of male and female sex roles on which patriarchy depends.) Access to abortion and access to trans healthcare are often attacked in similar ways: principally by overstating the incidence and likelihood of regretting either process, and an intense, disproportionate focus in the media on the stories of individuals who do regret their personal choices, as a way to undermine the principle of choice generally. Only about 5 per cent of women experience any degree of regret over their abortion. Multiple studies show the regret rate for gender reassignment surgery is even lower: about 0–2 per cent. Despite this, the fear of regret has become a powerful tool used to justify the delay or withholding of treatment. Little wonder, then, that it is conservative politicians who attack trans healthcare and women’s reproductive rights in the same breath.

- What we choose to define (and stigmatize) as ‘mental illness’ is itself a matter of politics. For instance, our perception of homosexuality as an identity instead of a disorder is a relatively recent development, made possible by decades of campaigning to depathologize it.

- Both trans and cis patients alike have good reason to fear the increasing NHS reliance on the private sector, which drives up costs and introduces a profit motive to healthcare, including gender identity services and surgeries. There is an irony here: it is generally conservatives who make specious claims about money-making schemes preying on trans people, but, in fact, it is conservatives’ own policies of cuts and privatization that actually allow the private sector to behave vampirically.

- Historical accounts of gender-variant people who lived in a social role different from the one assigned to them at birth occur in almost every recorded human culture. Sometimes, they lived their lives with the encouragement and licence of their community, which recognized the existence of a third gender – or even several other genders – beyond man and woman; sometimes, their perceived ‘transgression’ of gender norms was understood to merit punishment.

- The same hormone therapies that today are associated with helping trans people – the use of feminizing oestrogen for trans women and masculinizing testosterone for trans men – were used by endocrinologists in the middle decades of the twentieth century in attempts to ‘cure’ sexual inverts and intersex individuals, by administering hormones to ‘remedy’ the imbalance which caused their ‘disorder’. Homosexual females, for instance, would be treated with oestrogen. Homosexual males were sometimes treated with testosterone and, in some cases, with oestrogen in order to chemically castrate them and prevent them acting on their desires. In the 1950s such hormonal ‘cures’ for sexual and gender variance diminished (largely because they didn’t work), only to be replaced by psychiatric and aversion therapies – the underlying belief in sexual inversion and disorder remained. It must be stressed that the non-consensual, coercive and violent use of hormones to interfere with the bodily integrity of LGBTQ+ people and those born with intersex conditions destroyed countless lives and should be considered a stain on the history of Western medicine. This shared historical experience is also a point of unity for trans people and cisgender lesbians, gays and bisexuals, demonstrating our shared struggle against our pathologizing and mistreatment over the past century and more.

- Given the British media’s recent pained wrangling with the very idea of gender affirmation as a potential ‘slippery slope’, the fact that more straightforward access to medical transition and legal gender recognition was available during the Second World War than is often the case today is astonishing. The mainstream media’s presumption that strict ‘controls’ on transition are and have always been necessary relies on the suppression, and ignorance, of trans medical and legal history.

- It is important to realize that the framing of trans people as ‘parodies’ who reinforce stereotypes cruelly disregards the ways in which those same British trans people – whose gender expression, dress, hairstyles, makeup preferences and so on have, it clearly needs to be said, always varied as much as their cisgender counterparts’ – have spent the past fifty years being coerced into narrow gender conformity by their doctors, then mocked and derided as too stereotypical and regressive by cis onlookers. If it sounds like a catch-22, it’s because it is.

External links

This article is issued from Wikiquote. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.